Introduction

Effective perioperative pain management is essential for ensuring patient comfort, promoting recovery and reducing complications.

The goals of perioperative pain management, as set out by the Faculty of Pain Medicine, are to:

1. Reduce pain and ensure continuity of analgesic care from the operating theatre, through recovery, and onto the ward.

2. Ensure management is individualised according to the surgical procedure, the phase of recovery, the patient’s needs, their overall health and their preoperative analgesic requirement and thus tolerance.

3. Provide effective pain control to facilitate the patient’s return to normal daily activities such as eating, drinking, moving, and walking.1

Optimal perioperative pain management involves a multimodal approach involving both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods.1-2

Non-pharmacological methods

Non-pharmacological strategies are a key adjunct in perioperative pain management, with the potential to not only alleviate pain but also to reduce the reliance on pharmacological methods and thereby minimise associated adverse effects.

Although there is limited evidence, these interventions are increasingly recognised as a valuable part of a multimodal analgesic approach.

Patient education

Preliminary studies indicate that patients who receive preoperative education about expected postoperative pain and the potential side effects of analgesic medications report lower pain levels and fewer adverse effects when compared to control groups.3

This is standard practice for all patients, regardless of the surgical procedure.

Positioning

Positioning is an important consideration during both the intraoperative and postoperative periods.

During surgery, the patient should be positioned carefully using support devices such as pillows and gel pads to minimise the risk of pressure damage and positional pain. Effective positioning not only helps prevent pressure damage, which can contribute to postoperative pain, but also supports earlier mobilisation.

This is standard practice for all patients, regardless of the surgical procedure.

Cold or heat therapy

Cryotherapy involves the application of cold therapy (e.g. ice packs or specialised equipment) to reduce inflammation and pain. Heat therapy involves applying heat (e.g. heat packs or specialised equipment) to reduce stiffness or pain.

Initial studies have shown that cryoanalgesia with opioids was more effective as a method of postoperative pain relief than opioids alone.4 In the UK, this is not commonly used and does not form part of routine practice, except in specialist centres in specific conditions. It is thought that there is a role for heat therapy in pain relief postoperatively, but there is limited evidence.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

TENS is a non-invasive analgesic method that uses a device to deliver low-voltage electrical impulses through electrodes placed on the skin. It works by stimulating sensory nerves, which can interfere with pain signal transmissions to the brain, ultimately reducing the patient’s perception of pain.

Studies have shown that utilising TENS as a component of multimodal postoperative pain management is beneficial to the patient in reducing their pain intensity at rest and their requirement for opioid medication in the immediate and 24-hour postoperative period.5

TENS is not routinely used but may be considered as part of postoperative pain management, particularly for patients with a history of chronic pain.

Pharmacological methods

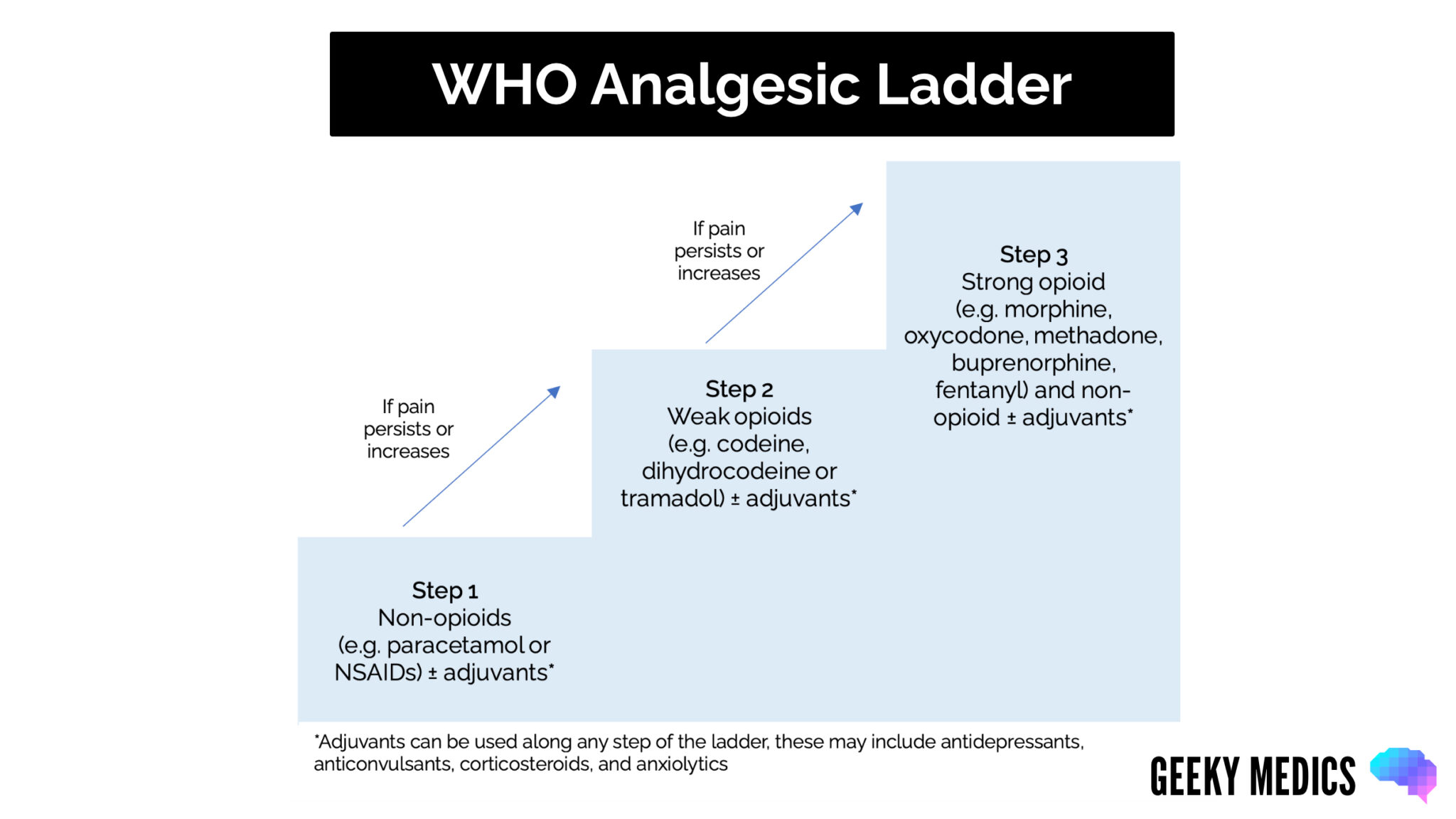

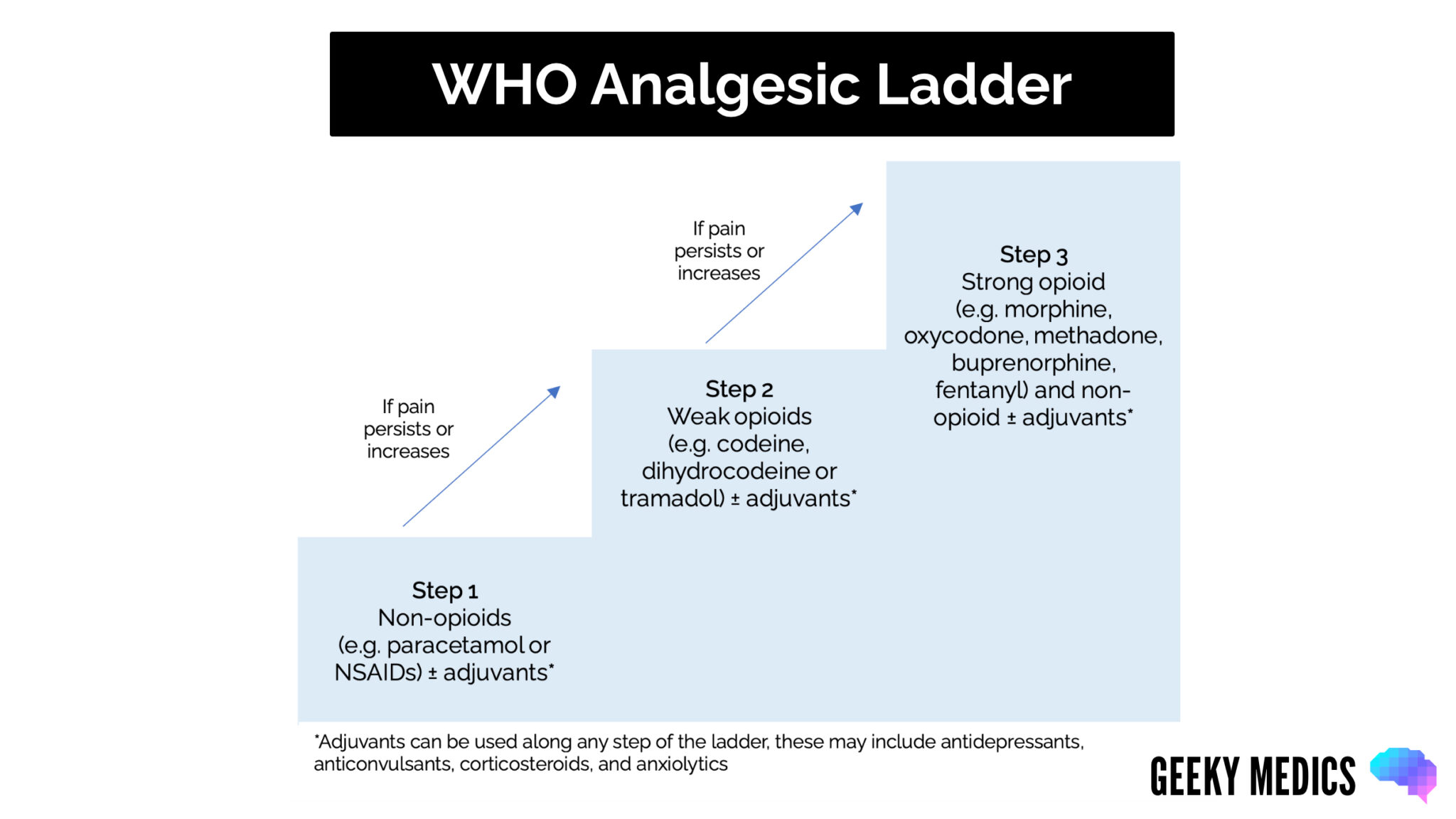

Pain ladder

The WHO analgesic ladder is a stepwise framework for managing pain. Although initially developed for cancer pain, it is now widely used for pain management, including in the perioperative period.6

Preoperatively

In anticipation of surgery, oral paracetamol can be administered. Oral paracetamol is more cost and environmentally effective than intravenous (IV) with the same analgesic outcomes.

Intraopereratively

Intraoperative analgesia is guided by clinical judgement and hospital guidelines. A potent opioid, such as fentanyl, is often administered prior to induction to blunt the hypertensive response during intubation.

A typical regime includes paracetamol (ensuring sufficient time between doses) with or without an NSAID (if not contraindicated) alongside further doses of a potent immediate-release opioid, such as fentanyl or morphine, as required.2

Postoperatively

Analgesia is typically given intravenously until the patient can tolerate oral intake. In the recovery environment, intravenous opioids such as fentanyl or morphine can be administered under close supervision. These are not given in the ward setting unless as part of patient-controlled analgesia or as a specific breakthrough dose given under medical supervision.

Once tolerating oral intake, regular paracetamol and NSAIDs (if not contraindicated) with either a regular or as required opioid (often oral morphine) are used. Immediate-release preparations of opioids are preferred for acute pain, as they provide better pain control and are safer in the acute setting.2

A numerical pain score can be used to assess the patient’s pain, typically from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain), with the choice of analgesia guided by their pain score.

Opioids and safe discharge

Opioids should be reduced following surgery as quickly as pain allows. This may often be the first postoperative day for many procedures. Patients should not be discharged on newly commenced strong opioids without a senior pain team review.

If pain relief is needed at discharge, patients should be given clear guidance on how to take it safely, how to reduce or stop it when appropriate, how to dispose of any leftover medication, and be warned about the risks of driving or using machinery while taking opioids.1

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA)

This method allows patients to self-administer a preset dose of intravenous strong opioids by pressing a button. The machine is programmed to administer only a fixed amount at a predetermined interval.

This is typically morphine or fentanyl (preferred in renal impairment), with the dose and lockout time varying by locality. An example may be fentanyl 40 micrograms, with a 10-minute lockout.

Generally, a PCA is used for major procedures where pain is expected to be moderate to severe, or where other analgesic options have been tried and failed. The anaesthetic team typically makes the decision to use a PCA.

A PCA requires regular close monitoring, and supplemental oxygen may be necessary, particularly if the patient is at increased risk of respiratory depression or has underlying cardiorespiratory disease (e.g. obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

Whilst using PCA, patients must not be co-prescribed opioids by any other route for the risk of inadvertent overdose.

Regional techniques

Regional anaesthesia has become an important part of perioperative pain management. It can provide effective, site-specific analgesia whilst minimising systemic opioid requirements. There are different types, which are outlined below.

Nerve block

This technique uses local anaesthetic to temporarily block nerve activity, by either injecting local anaesthetic around an individual nerve (e.g. femoral nerve block), a nerve plexus (e.g. brachial plexus block), or by blocking a plane (a potential space between muscle or fascial layers), typically under ultrasound guidance. This is normally performed in the anaesthetic room before the surgery begins.

A single dose at the time of surgery can be used; however, more effective pain relief over several postoperative days is achieved by placing a catheter next to the nerve or plexus at the operation site and subsequently administering a continuous infusion of local anaesthetic. Pumps used for this are often elastomeric, requiring no electric power and thus improving patient mobility.

There are small risks of local anaesthetic toxicity and intravascular local anaesthetic effects.

Epidural

This involves injecting local anaesthetic +/- opioid into the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord. A catheter may be inserted to allow analgesia to be given postoperatively, which can be used as a continuous infusion or as a form of patient-controlled analgesia.7

Common surgical procedures where an epidural may be used include major abdominal surgery (e.g. laparotomy), spinal surgery or major bilateral limb surgery.

Epidurals can result in hypotension or a high block (local anaesthetic affecting spinal nerves above T4), and patients must be monitored and cared for in a ward or high dependency areas by staff familiar with epidurals and their potential complications.

Spinal

This technique involves injecting medication into the subarachnoid space of the spinal canal. It is typically given as a single dose of local anaesthetic +/- opioids, before surgery. Local anaesthetic provides intraoperative anaesthesia, while opioids (e.g. diamorphine) are highly effective in delivering 24-48 hours of pain relief.

In many centres, spinal anaesthesia has replaced the use of epidurals for standard perioperative analgesia in laparotomies, and is standard for minimally invasive but significant intra-abdominal procedures (e.g. laparoscopic or robotic colon resections).

Following spinal opioids, caution should be observed with further opiate administration, although a fentanyl PCA would often be provided for further postoperative analgesia. This group of patients should be cared for in areas familiar with these techniques and the observations required.

Local anaesthetic infiltration

This involves local anaesthetic (usually lidocaine or bupivacaine) being injected at the surgical site, sometimes with adrenaline to prolong the effect. This is performed by the surgical team at the end of the operation.

Common procedures where this may be used are minor surgical procedures (e.g. lipoma removal or skin excisions) and abdominal surgery.

Other pharmacological options

Gabapentinoids (e.g. gabapentin or pregabalin) may be considered in patients with neuropathic pain or following spinal surgery.2 When used, they are typically given as a single preoperative dose or a short postoperative course. Evidence supporting their effectiveness in postoperative pain management is limited, and therefore, they are not commonly used. Close monitoring is required, particularly when co-prescribed with opioids, due to risks of sedation and respiratory depression.

Ketamine is sometimes used following major surgery or in opioid tolerant/sensitive or chronic pain patients.2 Because it requires close monitoring, its use should be restricted to high dependency areas where staff are familiar with the drug and its potential complications.

Specialist agents such as these should only be prescribed by specialist pain teams or the anaesthetic team.

Reviewer

Dr Angus Vincent

Consultant in Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine

Editor

Dr Jamie Scriven

References

- Faculty of Pain Medicine. Surgery and Opioids: Best Practice Guidelines. 2021. Available from: [LINK].

- NICE. Perioperative care in adults. 2020. Available from: [LINK].

- Patil JD, Sefen JAN, Fredericks S. Exploring Non-pharmacological Methods for Pre-operative Pain Management. Frontiers in Surgery. 2022. Available from: [LINK].

- Park R, Coomber M, Gilron I, et al. Cryoanalgesia for postsurgical pain relief in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine and Surgery. 2021. Available from: [LINK].

- Viderman D, Nabidollayeva F, Aubakirova M, et al. The Impact of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) on Acute Pain and Other Postoperative Outcomes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024. Available from: [LINK].

- World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief. 1986. Available from: [LINK].

- Faculty of Pain Medicine. Best Practice in the Management of Epidural Analgesia in the Hospital Setting. 2020. Available from: [LINK].

Discover more from Bibliobazar Digi Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.