Introduction

The Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (eFAST) is a rapid bedside ultrasound protocol that can be incorporated in the evaluation of patients with blunt or penetrating trauma to the torso.1

Building on the original FAST exam, which evaluates for free fluid in the abdomen and pericardium, the eFAST also includes views of the lungs to detect pneumothorax and haemothorax.

In practice, it is recommended that eFAST should not take longer than 5 minutes to complete.

Ultrasound code of conduct

- POCUS is rarely used to rule out pathology

- POCUS should be used in accordance with local hospital guidelines, which often require credentialing or accreditation

- Ensure patient consent, privacy and comfort throughout

- Document/capture your findings

- Seek help if you are unsure of any findings

- Ultrasound is a radiation-free method of imaging, so the risks to the patient are minimal

- Always use POCUS as part of a wider clinical examination

We recommend reading the Geeky Medics article on the basics of ultrasound in conjunction with this eFAST article.

Indications

Indications for the eFAST include:

- Haemodynamically unstable trauma patient

- Haemodynamically stable blunt and/or penetrating abdominal and/or thoracic trauma

- Unexplained hypotension or shock in a patient without trauma

Considerations

eFAST is quick, but should not delay time-sensitive interventions, e.g. fluid resuscitation

A scan is positive if any free fluid is visualised. However, a normal eFAST does not exclude all injuries, and so should not delay definitive imaging (e.g. CT) or surgical intervention, if clinically indicated.1

Limitations

The eFAST is less sensitive in the setting of penetrating trauma than blunt trauma due to air entering the peritoneal or pleural spaces. Air does not allow ultrasound to penetrate deeper tissue.

Sensitivity is operator dependent and both false positives and negatives can arise. Furthermore, a positive result does not localise the bleeding to a specific organ. Therefore, the eFAST should not be used as a stand-alone examination tool.

The eFAST requires a minimum of 100 mL of fluid for visualisation of abdominal pathology and a minimum of 20 mL for chest pathology, meaning smaller collections of fluid may go undetected.2

Relevant anatomy

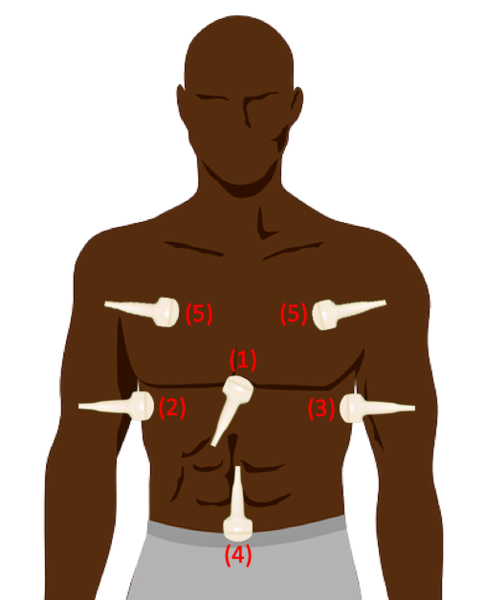

The eFAST assesses key anatomical cavities where fluid or air can accumulate in trauma.

The cardiac subcostal or parasternal long axis views allow visualisation of the heart and pericardial space for effusion/tamponade.

In the right upper quadrant (RUQ), the probe targets the hepatorenal pouch of Morrison, the peritoneal potential space between the liver and right kidney, a common site for free fluid. The left upper quadrant (LUQ) assesses the splenorenal recess and the surrounding area.

The pelvic view evaluates the rectouterine pouch in females or the rectovesical pouch in males, for pelvic free fluid.

Scanning anterior chest points assesses for pneumothorax or haemothorax by examining pleural sliding and fluid between the lung and chest wall.

Gather equipment

Collect all equipment needed for the exam and place it within reach at the patient’s bedside:

- Non-sterile gloves

- Gown or disposable apron

- Ultrasound machine

- Curvilinear probe

- Ultrasound gel

- Probe cover (optional)

The curvilinear or cardiac probe can be used for the eFAST exam, as they both allow for adequate image depth and resolution in all areas examined. This removes any need to switch probes mid-exam.

Introduction

Wash your hands using alcohol gel. If your hands are visibly soiled, wash them with soap and water.

Don PPE as appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient including your name and role (where possible).

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Where possible, briefly explain what the procedure will involve using patient-friendly language.

Example explanation

“Today I need to perform an ultrasound scan of your abdomen and chest to view your internal organs. This will help us to plan your ongoing management to the best of our ability. The procedure may feel a little uncomfortable, but it shouldn’t be painful. You will need to be exposed from the waist upwards, and we can help if needed. Does this all sound okay with you?”

Gain consent to proceed with eFAST (where possible).

Check if the patient has any allergies (e.g. latex or ultrasound gel).

Expose the patient entirely from the waist upwards. Female patients may keep their bra on if it does not obstruct the scan sites. A chaperone should be offered where appropriate.

Position the patient supine.

Ask if the patient has any pain before beginning.

Preparing the ultrasound machine

1. Turn the ultrasound machine on.

2. Select the appropriate preset; ‘FAST’ or ‘abdominal’ are commonly used, but this varies by machine.

3. Select the curvilinear/cardiac probe and ensure it is connected to the machine.

4. Disinfect the probe with a universal disinfectant wipe.

5. Position the patient supine if not so already (and if safe to do so).

6. Expose the patient from the waist upwards.

7. If you are right-handed, position yourself on the right side of the patient (if possible).

8. Place the ultrasound machine on the other side of the patient (if possible).

9. Don probe cover (optional) and apply gel to the ultrasound probe.

10. Optimise the depth and gain.

If possible, adjusting the bed to place the patient in the Trendelenburg position and/or with their arms behind their head can improve the sensitivity of the examination.

Ultrasound views

The recommended sequence of eFAST views varies in the literature, based on the mechanism of injury and the risk of finding pathology.

In this guide, we begin with the cardiac views, as detecting pericardial fluid is a top priority due to its potentially life-threatening implications.

Cardiac

The cardiac view in eFAST helps detect fluid in the pericardial cavity, which can be life-threatening if left untreated. Any echocardiographic view of the heart can be used for this step, as all are able to visualise the pericardium. In practice, the parasternal long-axis (PLAX) and subcostal views are most commonly used due to their ease of acquisition.

The two clinical questions you should aim to answer are:

- Does the patient have fluid around the pericardial cavity?

- Is there cardiac movement?

Parasternal long axis (PLAX)

1. Position the patient supine; if tolerated, a slight left lateral position can improve the view.

2. Place the probe on the left sternal border at the 3rd or 4th intercostal space.

3. Orient the marker towards the right shoulder tip.

4. Optimise the image by adjusting depth and gain to visualise the heart and surrounding pericardial space.

5. Assess for pericardial fluid, which appears as an anechoic (dark) stripe around the heart, and evaluate overall cardiac motion.

Subcostal

1. Position the patient supine; if possible, ask them to bend their knees to relax the abdominal wall.

2. Hold the probe in an overhand grip, with the marker oriented to the 3 o’clock position.

3. Apply a generous amount of gel just below the xiphisternum.

4. Place the probe firmly under the xiphisternum, applying downward and forward pressure so the beam penetrates sufficiently into the abdomen.

5. Fan the probe upwards to visualise the liver and all four chambers of the heart.

6. If the view is suboptimal, slide the probe slightly to the right of the xiphisternum, using the liver as an acoustic window to improve image quality.

- Asking the patient to inhale may also bring structures into view.

7. Assess for pericardial fluid by carefully fanning through the cardiac silhouette.

Right upper quadrant (RUQ)

The key structure assessed in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) is the pouch of Morrison, located between the liver and the kidney.

If possible, raise the patient’s arms above the head to widen the rib spaces, and ask the patient to deeply exhale to move the diaphragm inferiorly for better organ visualisation.

1. Hold the probe in an overhand grip, aligned longitudinally with the marker pointing towards the patient’s head.

2. Place the probe on the patient’s right side, along the mid-axillary line at approximately the 10th – 11th intercostal space. Use the costal margin as a guide and position the probe just above it.

3. Depending on the patient’s body habitus, slide the probe slightly caudally to optimise the view.

4. Adjust depth and gain until both the liver and kidney are clearly visualised.

5. Identify the hyperechoic line separating these structures, which represents the pouch of Morrison.

6. Fan the probe slowly in both directions to examine the entire pouch, looking carefully for any fluid collections.

7. Extend your assessment to the tip of the liver and the suprahepatic (subphrenic) space to ensure no pockets of free fluid are missed.

Left upper quadrant (LUQ)

The key structure assessed in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) is the splenorenal recess, located between the spleen and kidney.

If possible, raise the patient’s arms above the head to widen the rib spaces, and ask the patient to deeply exhale to move the diaphragm inferiorly for better organ visualisation.

1. Hold the probe in an overhand grip, positioned longitudinally with the marker pointing towards the patient’s head.

2. Place the probe on the patient’s left side, along the posterior axillary line at the 7th – 8th intercostal space.

3. Keep your knuckles in contact with the bed to angle the probe correctly, as the spleen lies posteriorly.

4. The spleen can be difficult to visualise due to the ribcage; improve the view by rotating the probe to match the angle of the rib spaces.

5. Once obtained, identify the hyperechoic line between the spleen and kidney, the splenorenal recess.

6. Fan the probe in both directions to assess for any anechoic (dark) fluid within the recess.

7. Extend the assessment to the splenic tip and perisplenic (subphrenic) space to ensure no free fluid pockets are missed.

Pelvis

The key structures assessed in this view are the rectouterine pouch (pouch of Douglas) in females and the rectovesical pouch in males.

1. Identify the pubic symphysis by palpation as your landmark.

2. Hold the probe longitudinally, with the marker pointing towards the patient’s head, and place it in the midline just above the pubic symphysis.

3. Rock the probe downward to obtain an optimal image demonstrating the bladder, uterus (in females) or prostate (in males), and rectum.

4. Examine the rectouterine/rectovesical space between the rectum and uterus or prostate.

5. Fan the probe carefully to assess for any anechoic (dark) free fluid.

6. Rotate the probe 90 degrees into a transverse orientation, with the marker pointing towards the 3 o’clock position.

7. Reassess the pouches in this plane, once again fanning through to look for free fluid.

Thorax

The key pathologies assessed in the thorax are pneumothorax or haemothorax.

While structured methods for lung ultrasound have been developed (e.g. BLUE protocol), the number of areas to scan in the lung field varies between operator preference and clinical context.3 In an eFAST context, anterior chest points are typically prioritised.

Anterior chest points

At each anterior chest point, the curvilinear probe is held in the dominant hand with a ‘pencil’ grip, with the probe indicator facing the patient’s head.

Place the probe in the intercostal space at the anterior chest points, and aim to achieve the ‘batwing’ sign.

The ‘batwing sign’ refers to the appearance of the rib shadows and pleural line, resembling the wings of a bat, when the probe is placed longitudinally on the chest wall. This sign helps confirm correct probe placement.

Lung sliding

Reduce the depth to approximately 5 cm and bring the pleural line into the centre of the image; this will allow for maximum definition.

During normal ventilation, a minute layer of pleural fluid allows the visceral and parietal pleura to slide against each other.

Any pathology that separates the pleural layers or prevents normal ventilation, such as pneumothorax or airway obstruction, will stop the movement of the parietal and visceral pleura, which will be evident as an absence of lung sliding.

In some cases, a region of lung sliding may be adjacent to a region of no lung sliding, described as a lung point or the exact boundary of the pneumothorax.

If ‘lung sliding’ is not completely visible, this can be confirmed using M-mode, which tracks a single scan line over a short period of time. Skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle above the pleural line are typically stationary during normal ventilation, while the pleura and the tissue below the lung move, creating the seashore sign.

With any pathology affecting lung sliding, the pleural line and lung tissue will also appear stationary, creating the stratosphere or barcode sign.

To complete the procedure

Document the procedure by saving images of the standard views, plus any additional images of pathology.

Explain to the patient that the procedure is now complete (if appropriate).

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

Document findings in the patient’s notes.

Interpretation of eFAST results

Clinical decision-making based on eFAST results will vary depending on the nature of the injury and the local guidelines. As a general rule, a patient who is haemodynamically unstable with a positive eFAST will go straight to emergency surgery (either thoracotomy, laparotomy, or both); with other patients having a mix of observations or other forms of imaging.

More advanced healthcare systems have additional tools for arresting major haemorrhage (e.g. REBOA, SAAP, pelvic embolisation) that may be deployed depending on availability.

A quick start guide

1. Start by recognising this is an unstable patient, and you are looking for acute life-threatening pathology

2. Prepare the patient

3. Prepare the equipment

4. Obtain the scans in sequence, assessing for the presence of fluid in the pericardial and peritoneal spaces

5. Optimise your image by manipulating depth and gain

6. Complete the scan by documenting the procedure and your findings

7. Correlate your scans with other objective clinical assessments and scans

8. Follow the ultrasound code of conduct

Reviewer

Dr Segun Olusanya

Consultant in Intensive Care Medicine

Editor

Dr Jamie Scriven

References

- Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (EFAST). The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2004. Available from: [LINK].

- Savatmongkorngul S, Wongwaisayawan S, Kaewlai R. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma: current perspectives. Open Access Emergency Medicine. 2017. Available from: [LINK].

- Lichtenstein DA, Mezière GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008. Available from: [LINK].

Image references

- Figure 1. OpenStax. Body Cavities Frontal view. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY 3.0].

- Figure 2. Connexions. Serous Membrane. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License:

- [CC BY 3.0].

- Figure 4. EUSKALANATO. Female pelvic cavity. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0].

- Figure 5. EUSKALANATO. Male pelvic cavity. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC-SA 2.0].

- Figure 6. Cancer Research UK uploader. Diagram of the lung showing the pleura. License: [CC BY-SA 4.0].

- Figure 7. Armstrong VM. EFAST View. License: [CC BY-SA].

- Figure 10. Alerhand S. Cardiac Tamponade. The POCUS Atlas. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 13. IUEM Ultrasound. Pericardial Effusion With Hematoma. The POCUS Atlas. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 16. Siegel G and Kidon M. RUQ +FAST. The POCUS Atlas. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 19. Bowra J. Positive FAST – LUQ. The POCUS Atlas. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 22. Bowra J. Positive FAST Pelvis – Transverse. The POCUS Atlas. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 27. Peter Gutierrez. The Pocus Atlas. Lung point. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

- Figure 29. Dr. Eric Roseman. The Pocus Atlas. Pneumothorax: M-mode: Seashore vs Barcode. Adapted by Geeky Medics. License: [CC BY-NC 4.0].

This article was originally authored by Valerie M. Armstrong and Christopher R. Woodard and subsequently updated by Ephraim Chappidi.

UltraLearn

The UltraLearn Project is a student-led, clinician-supervised initiative whereby students across UK medical schools gain confidence and interest in the basics of POCUS. Find out how you can join the community @ultralearnpocus on Instagram, X and LinkedIn.

Discover more from Bibliobazar Digi Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.