Taking a comprehensive constipation history is an important skill often assessed in OSCEs. This guide provides a structured framework for taking a history from a patient with constipation in an OSCE setting.

Background

Constipation is a common symptom encountered across all ages and clinical settings. When taking a history, it is important to remember that “normal” bowel habit varies between individuals, and patients may use the term constipation to describe different symptoms.

Constipation is typically defined as bowel movements that are problematic due to infrequent stools, difficulty passing stools, hard stools or a sensation of incomplete emptying of the bowels.

Causes of constipation

Constipation is frequently functional (without an identifiable structural or biochemical cause), but it can also occur secondary to a wide range of conditions, including obstruction, neurological disease and endocrine or metabolic disorders (e.g. hypothyroidism, hypercalcaemia).

The causes of constipation can be organised according to the surgical sieve.

Functional

- Low fibre intake

- Inadequate fluid intake

- Reduced mobility or inactivity

- Withholding stool (e.g. due to pain, embarrassment or poor access to toilets)

Structural/obstructive

Endocrine/metabolic

Neurological

Drugs

- Iron or calcium supplements

- Opioids

- Antimuscarinics (e.g. oxybutynin)

- Antidepressants (e.g. tricyclic antidepressants)

- Antipsychotics (e.g. clozapine)

- Antiepileptics (e.g. carbamazepine)

Other

Acute vs chronic constipation

Constipation may present acutely (e.g. dehydration, medication changes, acute illness or mechanical obstruction).

Chronic constipation typically refers to symptoms that have persisted for at least 3 months.

Opening the consultation

Wash your hands and don PPE if appropriate.

Introduce yourself to the patient, including your name and role.

Confirm the patient’s name and date of birth.

Explain that you’d like to take a history from the patient.

Gain consent to proceed with history taking.

General communication skills

It is important you do not forget the general communication skills which are relevant to all patient encounters. Demonstrating these skills will ensure your consultation remains patient-centred and not checklist-like (just because you’re running through a checklist in your head doesn’t mean this has to be obvious to the patient).

Some general communication skills which apply to all patient consultations include:

- Demonstrating empathy in response to patient cues: both verbal and non-verbal.

- Active listening: through body language and your verbal responses to what the patient has said.

- An appropriate level of eye contact throughout the consultation.

- Open, relaxed, yet professional body language (e.g. uncrossed legs and arms, leaning slightly forward in the chair).

- Making sure not to interrupt the patient throughout the consultation.

- Establishing rapport (e.g. asking the patient how they are and offering them a seat).

- Signposting: this involves explaining to the patient what you have discussed so far and what you plan to discuss next.

- Summarising at regular intervals.

Presenting complaint

Use open questioning to explore the patient’s presenting complaint:

- “What’s brought you in to see me today?”

- “Tell me about the issues you’ve been experiencing.”

Provide the patient with enough time to answer and avoid interrupting them.

Facilitate the patient to expand on their presenting complaint if required:

- “Ok, can you tell me more about your bowel habits?”

- “When you say constipation, what do you mean by that?”

Patients may use the term constipation to describe a range of symptoms, so it’s important to explore their understanding.

Using open questions helps establish a shared understanding of what they mean and how they describe their bowel habit.

Open vs closed questions

History taking typically involves a combination of open and closed questions. Open questions are effective at the start of consultations, allowing the patient to tell you what has happened in their own words. Closed questions can allow you to explore the symptoms mentioned by the patient in more detail to gain a better understanding of their presentation. Closed questions can also be used to identify relevant risk factors and narrow the differential diagnosis.

History of presenting complaint

Patients presenting with constipation often report a range of symptoms, including changes in stool form and frequency and associated symptoms (e.g. pain or bloating).

Exploring constipation in more detail

Onset and duration

Clarify how and when the constipation developed and how it has changed over time:

- “When did the constipation begin?”

- “Did it come on suddenly or get worse over time?”

- “How long have you been experiencing constipation?”

Stool form and consistency

It is important to establish the consistency of the stool, as this helps determine the severity of constipation and can point towards an underlying cause:

- “Is the stool difficult to pass?”

- “Does the stool come out as small hard lumps?”

- “Is it bulky?”

- “Have you experienced any loose stools after a period of being constipated?” (loose stools after periods of constipation can indicate overflow diarrhoea)

- “Have you noticed if your stool floats?”

If the stool floats persistently and is pale, greasy or foul smelling, this can suggest steatorrhoea due to malabsorption or pancreatic insufficiency (e.g. chronic pancreatitis, coeliac disease).

Ask about stool consistency directly:

- “Are your stools hard and lumpy, or softer?”

- “Could you compare your stool consistency with this stool chart?”

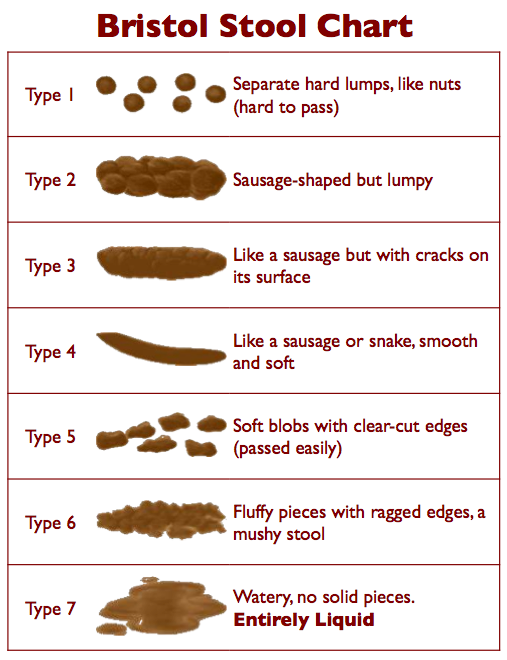

The Bristol Stool Chart

The Bristol Stool Chart is a visual tool used to classify stool consistency and form. Types 1 and 2 indicate hard, dry stools typical of constipation. It helps objectify how a patient describes their bowel movements and is particularly useful when assessing constipation.

Asking patients to identify their usual stool type can also help distinguish perceived constipation from overflow diarrhoea (where loose stool leaks around impacted faeces).

Stool frequency and pattern

Clarify how often the patient is opening their bowels and how this has changed from their usual pattern:

- “How often do you normally open your bowels? How often are you opening your bowels now?”

Asking about stool frequency and pattern helps determine whether this is an acute or chronic change.

Ask about the pattern and routine of bowel movements:

- “When in the day do you open your bowels? Has this changed over time?”

This helps establish the patient’s normal bowel pattern and how it has changed.

Associated symptoms

Ask if there are other symptoms associated with the constipation:

- “Are there any other symptoms associated with your bowel symptoms?”

Blood in the stool

It is important to ask about bleeding associated with opening the bowels and to clarify the details, as blood in the stool can indicate a number of pathologies:

- “Is there any blood in the stool?”

- “Is the blood mixed with the stool?”

- “Is the blood present on wiping or in the toilet pan?”

- “What colour is the blood?”

Blood on wiping can point towards haemorrhoids or an anal fissure, with haemorrhoids being a potential consequence of chronic constipation.

Blood mixed into the stool can point towards gastrointestinal pathology such as inflammatory bowel disease, diverticular disease, colitis or colorectal cancer.

Pain

Assess if there is associated pain in the perianal area:

- “Do you experience any pain in the back passage when opening your bowels?”

This can suggest haemorrhoids, abscesses, anal fistulas or fissures.

Ask if there is any abdominal pain:

- “Is there any pain in your tummy when opening your bowels?”

Abdominal pain may indicate faecal impaction, IBS, diverticular disease (often left iliac fossa pain) or colorectal cancer.

Straining

Ask if the patient experiences straining when opening their bowels:

- “Do you experience any straining when opening your bowels?”

Straining suggests stool passage is difficult and may be linked with dehydration or low fibre intake.

Faecal urgency

Ask if the patient experiences faecal urgency:

- “Do you feel you can’t control when you want to open your bowels?” (faecal urgency can point towards IBS or inflammatory bowel disease)

Stool colour and visible changes

Ask about stool colour and visible changes:

- “What colour is your stool?”

- “Is your stool pale brown?”

- “Are your stools dark brown or black?”

Pale stools can suggest issues related to bile production or flow and may be seen in pancreatic disorders, biliary obstruction and liver disease.

Darker stools can sometimes reflect dietary intake, and dark stools can also occur with iron supplementation. However, black, tarry stools can indicate melaena and should be treated as a red flag if the history is concerning.

Constipation red flags

It is important to recognise red flags that may suggest serious pathology. Keep these in mind throughout history taking in a patient presenting with constipation.

Red flags may include:

- Recent unintentional weight loss

- Rectal bleeding or melaena

- Symptoms of anaemia (e.g. fatigue, dizziness), which may reflect malignancy or ongoing blood loss

- Family history of colorectal cancer

- Loss of sensation in the perianal area or new neurological symptoms, which can suggest spinal cord compression or cauda equina syndrome

Ideas, concerns and expectations

A key component of history taking involves exploring a patient’s ideas, concerns and expectations (often referred to as ICE) to gain insight into how a patient currently perceives their situation, what they are worried about and what they expect from the consultation.

The exploration of ideas, concerns and expectations should be fluid throughout the consultation in response to patient cues. This will help ensure your consultation is more natural, patient-centred and not overly formulaic.

It can be challenging to use the ICE structure in a way that sounds natural in your consultation, but we have provided several examples for each of the three areas below.

Ideas

Explore the patient’s ideas about the current issue:

- “What do you think the problem is?”

- “What are your thoughts about what is happening?”

- “It’s clear that you’ve given this a lot of thought and it would be helpful to hear what you think might be going on.”

Concerns

Explore the patient’s current concerns:

- “Is there anything, in particular, that’s worrying you?”

- “What’s your number one concern regarding this problem at the moment?”

- “What’s the worst thing you were thinking it might be?”

Expectations

Ask what the patient hopes to gain from the consultation:

- “What were you hoping I’d be able to do for you today?”

- “What would ideally need to happen for you to feel today’s consultation was a success?”

- “What do you think might be the best plan of action?”

Summarising

Summarise what the patient has told you about their bowel symptoms. This allows you to check your understanding of the history and provides an opportunity for the patient to correct any inaccurate information.

Once you have summarised, ask the patient if there’s anything else that you’ve overlooked. Continue to periodically summarise as you move through the rest of the history.

Signposting

Signposting, in a history taking context, involves explicitly stating what you have discussed so far and what you plan to discuss next. Signposting can be a useful tool when transitioning between different parts of the history and it provides the patient with time to prepare for what is coming next.

Signposting examples

Explain what you have covered so far: “Ok, so we’ve talked about your bowel symptoms, your concerns and what you’re hoping we achieve today.”

What you plan to cover next: “Next I’d like to quickly screen for any other symptoms and then talk about your past medical history.”

Systemic enquiry

A systemic enquiry involves performing a brief screen for symptoms in other body systems which may or may not be relevant to the primary presenting complaint. A systemic enquiry may also identify symptoms that the patient has forgotten to mention in the presenting complaint.

Deciding on which symptoms to ask about depends on the presenting complaint and your level of experience.

Some examples of symptoms you could screen for in each system include:

- Systemic: fever, fatigue, unintentional weight loss (e.g. malignancy, inflammatory disease, infection)

- Gastrointestinal: abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting (e.g. bowel obstruction, malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome)

- Neurological: weakness, numbness, perianal sensory loss, lower limb weakness (e.g. cauda equina syndrome, spinal cord compression)

- Urogenital: urinary frequency, urgency, retention (e.g. pelvic floor dysfunction, rectal mass causing bladder compression)

Past medical history

Ask if the patient has any medical conditions:

- “Do you have any medical conditions?”

- “Are you currently seeing a doctor or specialist regularly?”

Ask if the patient has previously undergone any surgery or procedures (e.g. cholecystectomy, bowel resection):

- “Have you ever previously undergone any operations or procedures?”

- “When was the operation or procedure, and why was it performed?”

If the patient does have a medical condition, you should gather more details to assess how well controlled the condition is and what treatment(s) the patient is receiving. It is also important to ask about complications associated with the condition including hospital admissions (e.g. recurrent admissions for inflammatory bowel disease flares).

Examples of relevant medical conditions

Medical conditions relevant to constipation include:

- Irritable bowel syndrome: a functional gastrointestinal disorder associated with abdominal pain and change in bowel habit, which can include constipation

- Inflammatory bowel disease: although diarrhoea is more common, constipation can suggest complications such as strictures

- Hypothyroidism: constipation is often chronic and associated with other symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain and cold intolerance

- Colorectal cancer: can cause obstructive constipation if the tumour is in the colon or rectum and may be associated with weight loss and anaemia

- Anal fissures or haemorrhoids: often linked with straining, painful defecation and bleeding

- Muscular dystrophy: constipation may arise from weakness of abdominal and pelvic muscles, reducing straining ability and slowing bowel movements

- Psychiatric disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, anorexia nervosa): constipation can be related to reduced intake, dehydration, medications (e.g. antidepressants, antipsychotics) and neurological factors via the brain-gut axis

Allergies

Ask if the patient has any allergies and if so, clarify what kind of reaction they had to the substance (e.g. mild rash vs anaphylaxis).

Drug history

Ask if the patient is currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter remedies:

- “Are you currently taking any prescribed medications or over-the-counter treatments?”

If the patient is taking prescribed or over-the-counter medications, document the medication name, dose, frequency, form and route.

Ask the patient if they’re currently experiencing any side effects from their medication:

- “Have you noticed any side effects from the medication you currently take?”

- “Do you think your bowel symptoms started after you began taking any medication?”

Medication examples

Several commonly prescribed and over-the-counter drugs can slow gut motility or reduce stool water content, including:

- Opioids: slow gastrointestinal transit by reducing peristalsis (e.g. codeine, morphine)

- Antimuscarinics: inhibit smooth muscle contraction in the bowel (e.g. oxybutynin, hyoscine)

- Iron supplements: can harden stool and darken its colour due to unabsorbed iron

- Antidepressants: particularly tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline) and SNRIs (e.g. venlafaxine), can reduce gut motility

Ask about laxative use and duration. Chronic use, particularly of stimulant laxatives such as senna and bisacodyl, can lead to bowel dependence and paradoxical constipation.

Family history

It is important to ask if there is any family history of inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer or hereditary gastrointestinal conditions.

- “Have any of your family members been diagnosed with gastrointestinal problems or problems with the back passage?”

Clarify at what age the disease developed (disease developing at a younger age is more likely to be associated with genetic factors).

If one of the patient’s close relatives is deceased, sensitively determine the age at which they died and the cause of death:

- “I’m really sorry to hear that, do you mind me asking how old your dad was when he died?”

- “Do you remember what medical condition was felt to have caused his death?”

Social history

Constipation can significantly affect daily life and is often influenced by lifestyle factors.

General social context

Explore the patient’s general social context including:

- the type of accommodation they currently reside in (e.g. house, bungalow) and if there are any adaptations to assist them (e.g. stairlift)

- who else the patient lives with and their personal support network

- what tasks they are able to carry out independently and what they require assistance with (e.g. self-hygiene, housework, food shopping)

- if they have any carer input (e.g. twice daily carer visits)

Diet and fluid intake

Explore the patient’s diet and hydration:

- “How is your diet? Are you eating fruit and vegetables regularly?”

- “How much fluid do you drink in a typical day?”

Low fibre intake and inadequate hydration are common contributors to functional constipation.

Psychosocial factors

Explore whether stress, anxiety or low mood may be contributing to symptoms:

- “Have there been any recent stresses that might be contributing?”

- “How have things been in yourself recently, mood-wise?”

Exercise

Explore how regularly the patient exercises, as physical inactivity can reduce gut motility:

- “How active are you day to day?”

- “Do you manage to do any regular exercise?”

Smoking

Record the patient’s smoking history, including the type and amount of tobacco used.

Calculate the number of ‘pack-years’ the patient has smoked for to determine their cardiovascular risk profile:

- pack-years = [number of years smoked] x [average number of packs smoked per day]

- one pack is equal to 20 cigarettes

See our smoking cessation guide for more details.

Alcohol

Record the frequency, type and volume of alcohol consumed on a weekly basis.

See our alcohol history taking guide for more information.

Occupation

Ask the patient about their current occupation and typical daily routine. Sedentary roles with limited movement (e.g. office workers, truck drivers) can slow gut motility.

Closing the consultation

Summarise the key points back to the patient.

Ask the patient if they have any questions or concerns that have not been addressed.

Thank the patient for their time.

Dispose of PPE appropriately and wash your hands.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Constipation in adults. Available from: [LINK]

- NICE. Quality standard QS62: Constipation in children and young people. Available from: [LINK]

- Andrews A, St Aubyn B. Assessment, diagnosis and management of constipation. Nursing Standard. Available from: [LINK]

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Evaluation of constipation. Available from: [LINK]

Discover more from Bibliobazar Digi Books

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

![The Herbal Apothecary PDF Free Download [Direct Link]](https://bazarbiblio.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/The-Herbal-Apothecary-100-Medicinal-Herbs-and-How-to-Use-Them-PDF-Free-Download-1-1024x593.jpg)